The kidnapping in Mexico has changed. Nowadays they take you even for 5000 pesos: Saskia Niño de Rivera

Kidnapping is an established business in Mexico. Specialized gangs resemble precisely organized enterprises. We took a closer look at the subject with well-known local criminologist and crisis communication specialist Saskia Niño de Rivera.

Saskia Niño de Rivera worked, among other things, in a security agency as a negotiator with kidnappers. She has handled around forty cases in which she negotiated the extradition of victims of kidnappings. "It was interesting for me. And also, very hard, to be waiting for the call, to be waiting for the negotiation, and to make sure that the family followed your instructions. Because it's not that you pick up the phone and you negotiate, it's that dad or wife or grandfather or somebody is the one that transmits this message. So, all day long you are preparing that person for the call," she looks back.

Today, she mainly leads Reinserta, an organization that helps children and teens whose lives have been affected by violence and crime to get back to normal life. Last year, she published a book, El infierno tan temido: El Secuestro en México (The Dreaded Hell: Kidnapping in Mexico), in which she presents the testimonies of kidnapping victims and the perpetrators themselves. We met at her house in Ciudad de México at the end of the year to discuss the topic.

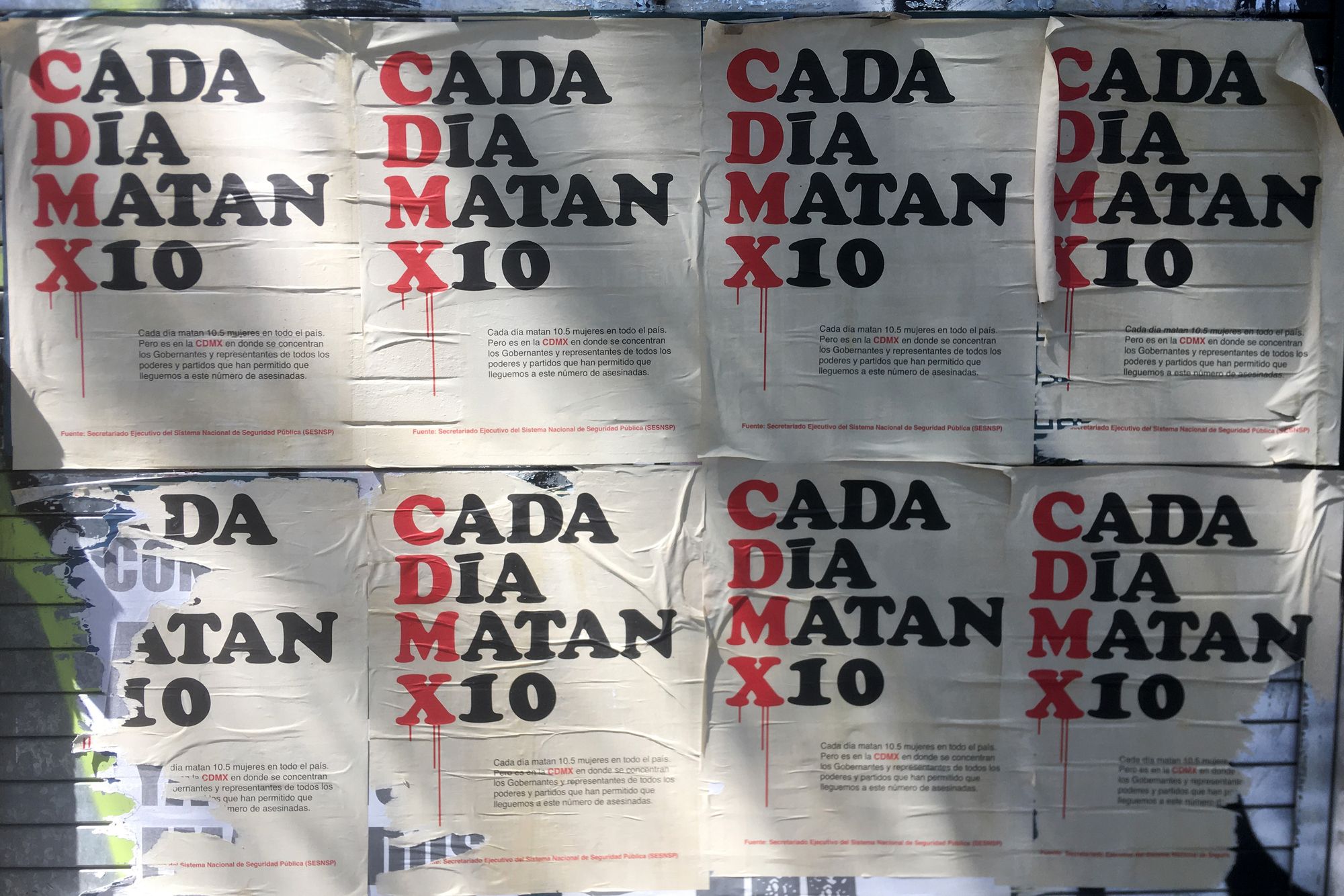

"In Mexico, we have become a country of numbers – everything is a number, isn’t it? Such a high percentage of kidnappings, such a high percentage of femicide, eleven women murdered every day... but we have stopped feeling what that implies," Niño de Rivera says of why she decided to write a trilogy in which each of the books bears the testimony of both victims and offender so that the numbers become actual human stories. "I want to put on paper that crime in Mexico is very violent, very dangerous, that it destroys families and entire lives," she says. "For me, it is very important that when we talk about justice, we understand the case in its totality,” she adds.

Going to the local police? Better not

One of the protagonists of the above-mentioned book, Helen, describes the 12 days spent in captivity as literally the equivalent of living in hell. She experienced physical and mental abuse, rape, humiliation, and the threat of physical liquidation. Eventually, they managed to ransom her and get her back home. But not without consequences.

Even though twenty years have passed, her soul bears deep wounds, the author of the book tells me. "Helen came from a Jewish family. To this day, when the fast of Gedaliah occurs during Yom Kippur and she has to avoid food according to tradition, she intentionally eats. It's her way of protesting because she's angry at God for allowing what has happened to her," Ms. Niño de Rivera says. Today, as a mother, Helen pretends to believe in God in front of her children, because she believes that believing in something is correct, but she has lost her faith after all that has happened to her.

Alberto was not released until after 290 days in captivity, during which time he did not speak a word and experienced practically no human contact. It went so far that at one point he simulated a suicide attempt in front of the cameras in his cell to attract attention and establish human contact after more than six months of separation. In his testimony, he refers to the kidnappers as a large group with good equipment and economic knowledge. From the beginning, the guards avoided any contact with him - communication was exclusively through printed notes. Immediately after the kidnapping, they used a scanner to check for a GPS chip or other locator device in the victim's guts. In the first few days, he was even given a printed questionnaire to fill out with 25 questions about his family and possessions. It was accompanied by a book, and on its pages, he found records of his every move over the past two months.

He, too, was able to be ransomed and returned home, but afterward, he had to be "reborn", as Ms. Niño de Rivera puts it. At home, his wife was waiting for him with a child who had no memory of him after almost a year of separation; they had to establish a de facto new relationship.

However, these cases are just a drop in the ocean. In the last four years, seven thousand people have been kidnapped in Mexico, and over a hundred thousand are currently missing. Yet only a fraction of kidnappings are reported because people fear vengeance or their loved ones being murdered in captivity. Specifically, only four percent of kidnappings are reported, and of these, Ms. Niño de Rivera says only half are successfully investigated. So, she advises relatives of abductees: If you have contacts in the upper levels of public security or the prosecutor, contact them. If you would be limited to the regular “ministério público”, don't denounce it. "The chances of them being connected to criminals are very high," she says.

Some gangs know from the beginning that they won't return the victim

In her book, the author looks at criminal groups that operated in the country between 1996 and 2006. In the cases described, we follow precisely orchestrated actions of professional gangs that almost exclusively went after selected victims from the highest classes, most often family members of powerful and wealthy people. They then demanded ransoms, which often ran into tens of millions of dollars. In the book, we then learn about the various practices by which the specialized kidnappers avoided detection. In particular, they strictly demanded all sorts of rules leading to the victim not being able to identify its abductors - there were always masks in the vicinity, the victim had to wear a hood, communication was in writing, and so on.

An equally sophisticated process also accompanied the negotiations, full of mental tricks and intrigues. If the victim and his or her loved ones cooperated as instructed and the ransom was handed over, the victim was dropped off in an unknown location with instructions on how to get home and a few coins for a taxi. If not, threats in the form of chopped-off ears or fingers were made. However, the victim's relatives also had to play their part, such as delaying the payment of the ransom - if they had delivered the money the very next day, it would have meant that they could have delivered much more, and the kidnappers would have immediately asked for a higher amount.

In the case of the specialized groups we learn about in the book, everything was carefully planned down to the last detail, each member of the gang had a specific role to play, and as long as the victim followed the instructions, they often treated them with respect and without violence.

"There are kidnappers who will tell you upfront, 'I'm not a murderer, I'm a kidnapper, and I keep my word,' so when the negotiation is over, the victim does come back," Ms. Niño de Rivera describes. "But there are also gangs that are dedicated to killing, they know from the beginning that they are going to end up killing their victims. To lower the risks. They do the whole kidnapping thing, they ask for money, and in the end, they don't return the victim. Other gangs look at the risk before returning the victim. Because any mistake can happen during captivity. For example, you entered the room with the victim and forgot to put the hood on. So, he saw you. And that is practically signing your death warrant," Ms. Niño de Rivera says.

With amateurs on the scene, kidnappings have become tough

The most famous kidnapper in Mexican history is Daniel Arizmendi López, alias El Mochaorejas (The Ear Chopper). He is largely to blame for making kidnapping fashionable in the 1990s, as well as the trend for abductors to use mutilation of their victims - in his case in particular, cutting off their ears to send to the relatives of the victims of kidnapping - in order to achieve a better negotiating position. Mochaorejas, though, was originally a police officer who was introduced to crime in the 1980s. His gang was reportedly responsible for the kidnapping of more than 200 people, and Arizmendi was caught in 1998 and sentenced to half a century in prison.

But times have changed since his era. A criminologist describes how kidnappings used to be much more targeted. "Before it was much more focused, much clearer who was at risk – men with such an income, with such a position, and so on. Today kidnapping has diversified in many ways. Nowadays there are gangs that kidnap because of what clothes you're wearing, what car you're driving, and so on. For example, I worked with a family whose daughter was kidnapped for ten thousand pesos," she says. (10,000 MXN = around 500 USD)