We know who kidnapped them and to where. Desperate relatives search at their own risk for the missing abductees in Mexico

Tens of thousands of missing people, a state apparatus on the payroll of drug cartels and mothers digging up the corpses of their children. Welcome to Mexico, a land of colours and contrasts.

No, this is not meant to be a criticism of Mexico. It's my second home, I adore it, and every day I see what wonderful, admirable and kind people live there. But it has its problems, like everywhere. And they need to be talked about too, because Mexico is not just about breathtaking beaches, majestic pyramids and the most famous cuisine in the world. Unfortunately, it's also a place of extreme crime and corruption.

Kidnapping as a pillar of the underground economy

They say they have nothing left to lose. That's why they're also doing everything they can to find their missing parents, children, brothers and sisters. Alive or dead. It doesn't matter. They don't want revenge. They just want a dignified end for their loved ones and peace for their own souls. They call themselves "the seekers" and have dedicated their lives to finding missing people.

Abductions are either directly for money - especially relatives of rich people, who are then forced to pay a hefty ransom - or also for money, but as an express kidnapping, where the victim is dragged to an ATM and forced to suck it dry. Or again, for money, but in the form of labour. The men go to marijuana plantations or secret laboratories, the women to brothels. You could say that kidnapping is one of the pillars of the Mexican underground economy.

I took a closer look at them in an interview with a well-known Mexican criminologist and negotiator in this article:

If you can't rely on the ordinary policemen on the streets in Mexico not to rob you, how can you ask for anything more from their superiors, the prosecutor's office or the government. The relatives of the kidnapped are learning this the hard way. As you will read in the testimonies below, the state is making fools of them, not communicating and sweeping their accusations and evidence under the carpet in broad daylight. Desperate people have no choice but to help themselves. They form search teams, learn forensic science, pinpoint areas where the missing might be. And then they investigate, searching brothels, hospitals and morgues or secret graves in the ground. Often, they find their loved ones there.

The prosecutor's office is connected to the kidnappers.

"We found evidence, we found a safe house (the term for cartel hideouts - author's note) , we know who kidnapped them and everything. But the prosecutor's office does nothing," Jessica Nalleli, who is searching for her brother Ricardo, told me last week. Along with about two dozen people with similar fates, they gathered that hot March morning at the Monument to the Disappeared (Glorieta de las y los Desaparecidos). The aim was to inform about their plans for May 10, which is Mother's Day in Mexico, and the so-called "madres buscadoras" ("seeker mothers") are using the occasion to call on the state to help prevent an increase in crime.

Ricardo Gomez Santos disappeared seven years ago in Acapulco. He and a colleague were on their way to work. Then they went missing. Or that's what the state apparatus says, as Jessica told me. "The prosecutor's office is connected to the kidnappers. Of course, yes, we know who kidnapped them, it was people from the state administration, they kidnapped them, we have evidence. We found my brother's car down the street from the prosecutor's office. We searched for it all day, and when we alerted the public, it suddenly turns up outside the prosecutor's office two hours later. Does that seem normal to you?"

The prosecutor's office reportedly defends itself by saying that it knows nothing about anything and that the brother's car just appeared out of nowhere. But Jessica doesn't believe them. "They say they have nothing. How do they have nothing? In our searches, we found photos, a ticket from the tunnel, safe houses, we saw surveillance footage. But they don't care, they just reject us," complains the young woman.

All the criminal reports they filed have disappeared, she says. "They tell us that they send them from place to place, but that's not true. They have simply been withdrawn from the archives," Jessica is clear, and she says she has an idea of what happened to her brother: according to her, he was taken to work in the opium fields, of which there are many in the mountains around Acapulco.

The state has many eyes that don't want to see.

"We are not the only case like this, there are many more in Acapulco," says Jessica, and her colleague Ethel Lozada Gonzales agrees.

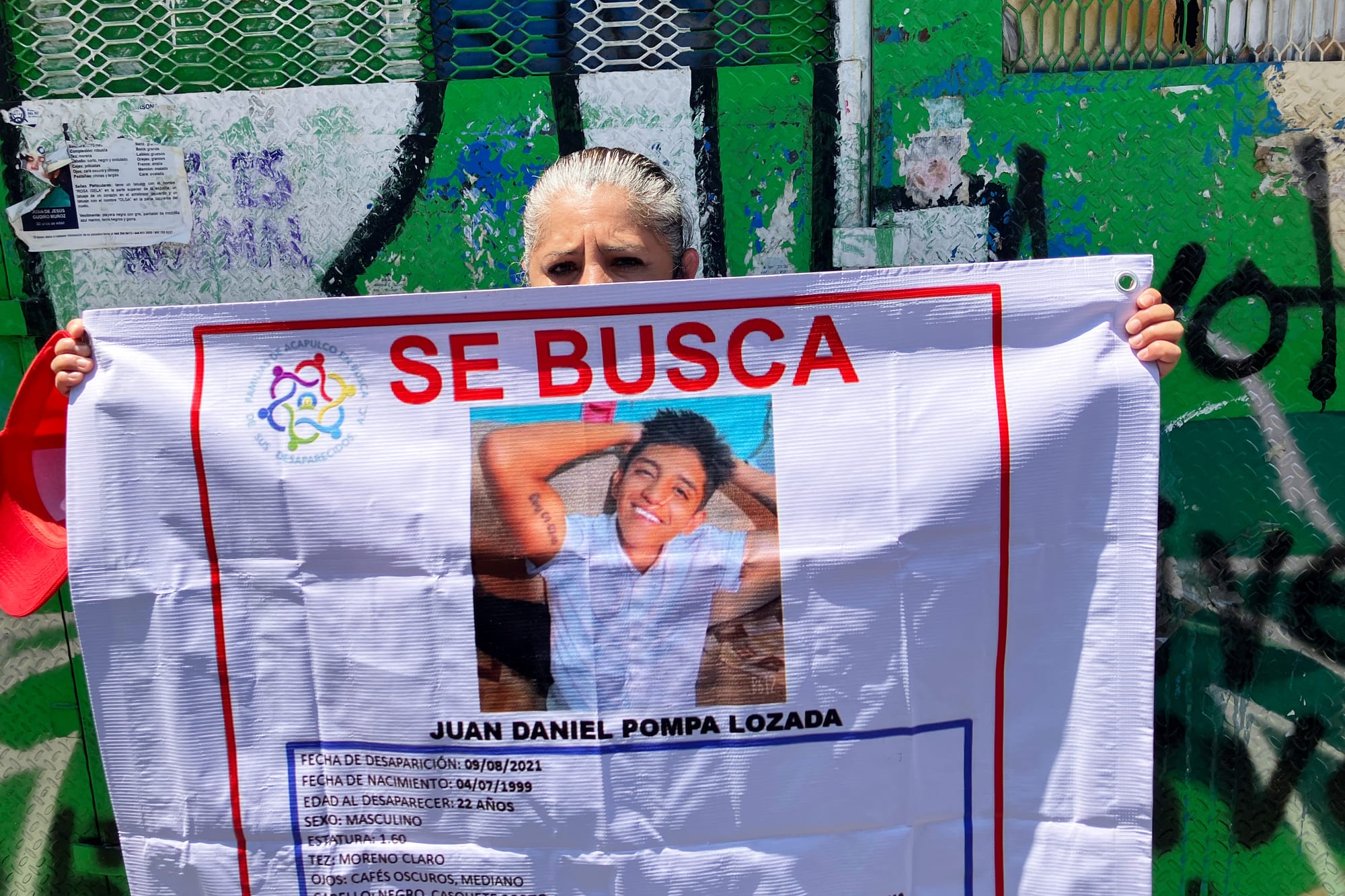

"My son also disappeared in Acapulco, on August 10, 2021, when he went looking for work," Ethel Lozada Gonzales tells me, "there was a shooting in which he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Unfortunately, there is evidence that he was detained by the police. I haven't heard from him since. I filed a criminal complaint, but I guess it has also disappeared because no one is answering me," she told me.

She shares the view about the involvement of the state apparatus in the abductions. "As my colleague said, the state administration is unfortunately involved in the disappearance of so many people," she stated.

In a little over a quarter of a year, Mexico will hold the biggest elections in the country's history. Over 20,000 representatives will be elected, including a new head of state, a two-chamber parliament and some minor municipalities. "We hope that the new political leadership will help us. There are so many disappeared, thousands and millions of them, and every day they are increasing," laments Ethel Lozada Gonzales. The state is working with a figure of 114,000 disappeared, but members of search groups say this figure is false and that in reality there are many more disappeared.

This year will be the first time in history that a woman will head Mexico. The candidates competing are the successor to the current president from the leftist Morena party and the candidate of a three-party coalition of right-wing parties. But Jorge Verasteguí is clear that that neither of them will bring change. "Either of the two candidates will follow in the same footsteps," said the brother of the disappeared Antonio.

"The state has many eyes that don't want to see," he said, summing up the essence of the problem, "it doesn't necessarily mean that the president sits at the same table as with the capos, but that the administration under his leadership tolerates many acts that allow criminal organizations to continue to operate."

Mexico has a long history of high crime rates. The steep rise began in 2006 with the declaration of the so-called war on narcos. That's when the army cracked down hard on the biggest trafficking aces, and some big names did indeed go down with great glory. But instead of calming down, it triggered an even bigger wave of bloodshed. Currently, over 30,000 people are murdered in Mexico every year.

"There is always a dark figure (a term referring to unreported crimes - author's note). We must remember that the dark figure for crimes involving deprivation of liberty is around 97 per cent. This means that we only have three percent of the officially reported missing," Jorge said, adding that there is no real figure for the number of disappeared people in Mexico.

"We're still hoping to find them," Ethel Lozada Gonzales believes, "he's my son and it hurts me a lot. All I really want is to find him. Let them tell us where our disappeared are. We're not looking for the people responsible, just let them tell us where they left our loved ones."